The unseen in the seen

Hyunjin Kim

Visual Artist & Photographer

Photographic Series · 7 Works · 2025

Email: kimhyunjinfo@gmail.com

Series Statement

The unseen in the seen is a photographic series that looks again at well-known paintings from Western art history through the lens of contemporary portraiture. Starting from works by René Magritte, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Caravaggio, Michelangelo, and Jan van Eyck, the series does not attempt to recreate the originals. Instead, it borrows their gestures, compositions, and atmospheres, and translates them into the bodies, clothes, and attitudes of people living now.

The images are intentionally familiar yet never fully graspable. They feel like echoes of paintings we think we’ve seen before, but the memory of the original and the photograph in front of us never quite line up. By making this slight misalignment visible, the series asks what we automatically assume we recognise, and what we fail to notice as we look.

At its core, the work is interested in how far we can read a person when not everything about them is clearly shown. I think of identity as something that appears not only in the face, but in posture, weight distribution, clothing, fabric, the position of hands and legs, the distance between bodies, and the objects and spaces that surround them. The sitters in these photographs are therefore less models imitating Old Masters and more contemporary figures negotiating historical images with their own bodies, clothes, and environments.

Famous images are often reproduced so many times that their context fades. The unseen in the seen brings these familiar paintings back onto present-day bodies and looks at how a contemporary gaze receives them, interprets them differently, and layers personal experience over them. Fashion, texture, gesture, and stance become ways of re-reading art history through the people who stand in front of the camera today, rather than decorative quotations from the past.

Ultimately, the series invites viewers to slow down and trace the small decisions within each frame – posture, clothing, gaze, spacing, background. In doing so, it encourages a reflection on how what is visible and what remains unseen are intertwined, and how both shape our sense of a person as well as our ongoing relationship to images from the past.

Artist Bio

Hyunjin Kim (b. 1994, Incheon, South Korea) is a London-based visual artist working primarily with photography and clothing. She studied photography and visual media in South Korea and Canada, and her work examines how people construct and perform identity through dress, gesture, and the way they appear in front of others. Moving between Seoul, Toronto, New York, London, and Paris, she develops visual arts projects that use photography and clothing, drawing on the visual language of fashion imagery while remaining independent from commercial work. Her recent series The unseen in the seen (2025) reimagines iconic art-historical images through contemporary bodies. She treats clothing not as a product but as a language and material of self-expression. Her work has been exhibited at Espacio Gallery (London), Bankley Gallery (Manchester), and Belfast Exposed, and featured in independent magazines that approach fashion as a site of cultural inquiry.

01. After The Son of Man (René Magritte, 1964)

The Screen of Man, Hyunjin Kim, 2025

The Son of Man, René Magritte, 1964

This photograph is a portrait of today – one that puts a screen where the face should be. I rework René Magritte’s The Son of Man as a contemporary full-length portrait: instead of a floating green apple, the sitter’s face is covered by a smartphone, its back showing the familiar bitten-apple logo. The suited body is fully visible — pinstripe jacket, tailored shorts, red tie knotted as a belt, red heeled sandals — but the most recognisable part of the person, the face, is erased by a glossy surface. The title The Screen of Man twists Magritte’s original and points to the thin digital layer that now sits between bodies and the way we are seen.

The photograph reflects on how self-image is staged today through devices, clothing, and gesture. The figure looks composed and work-ready, yet hides behind the very object that is supposed to stand in for them. Within the series The unseen in the seen, this image turns two questions back on the viewer: what do we choose to amplify when we appear in front of others, and what do we keep out of sight? And once the face has disappeared, how much of a person can still be read from posture, styling, and accessories alone? This picture acts as a small experiment inside the project, testing how far a body can speak when the face has stepped aside.

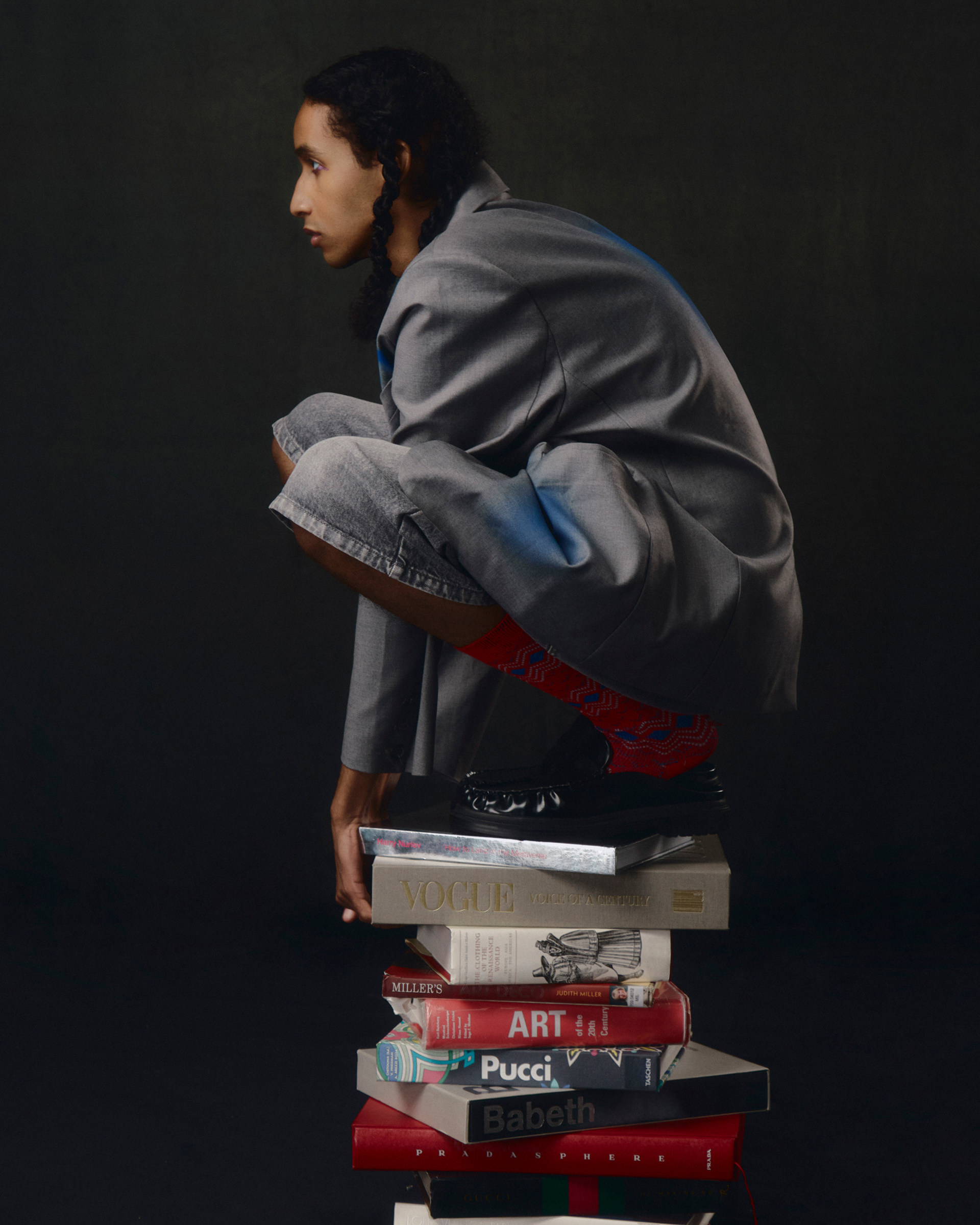

02. After The Librarian (Giuseppe Arcimboldo, 1566)

The Libra-rian, Hyunjin Kim, 2025

The Librarian, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, 1566

In this photograph, I reimagine Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s The Librarian as a contemporary portrait. Instead of presenting a face built from books, the sitter crouches on a stack of art volumes — titles on fashion, photography, and visual culture — carefully balancing their body as if knowledge and imagery were literally supporting their weight. Together, the body and the books form a compact, sculptural silhouette, so that the archive, posture, and identity seem to collapse into one.

The composition considers how a person’s sense of self today is shaped not only by lived experience but also by the visual worlds they consume: magazines, artworks, cultural references, and the histories we carry unconsciously. Within the series The unseen in the seen, this image highlights the invisible scaffolding of art history and visual memory that underpins how we present ourselves. It suggests that what we have seen — and what we continue to look at — quietly structures the way we inhabit our bodies in the present.

03. After Pietà (Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1498-1499)

Shared Pietà, Hyunjin Kim, 2025

Pietà, Michelangelo Buonarroti, 1498-1499

This photograph borrows the composition of Michelangelo’s Pietà and reconstructs it with two contemporary sitters. Instead of the Virgin cradling the dead body of Christ, a bare-chested man lies across the lap of a woman dressed in white. Her arms quietly receive and support his weight, but their expressions and gazes never offer the viewer a single, clear emotion. There is no church interior, no cross, no visible wounds; only the familiar structure of the pose remains, held by present-day bodies, clothing, and folds of fabric.

Here I wanted to use the same arrangement to evoke a different kind of weight — not divine sacrifice, but the weight that passes between people in everyday relationships. A body that hangs as if at the end of a long day, another that holds it without words, the temperature of skin where they touch: together these elements can suggest grief, comfort, care, burnout, and intimacy all at once. But the photograph refuses to fix who these two are to each other. They could be lovers, friends, family members, or colleagues briefly sharing a burden. The viewer is asked to build the story from small clues: the direction the weight falls, the angle of their limbs, the way her hands contain his body, the texture and drape of the white dress.

Within The unseen in the seen, this image tests how much meaning can still be generated when a well-known sculptural composition is carried almost intact into the present but stripped of its original context and religious language. A pose long tied to sorrow and devotion becomes, on contemporary young bodies, equally readable as getting through it together, quiet dependence, or a wordless moment of leaning on someone. In that expanded space of interpretation, the work folds back into the central question of the series: what is actually visible inside the frame, and what are we adding ourselves in order to make the scene feel complete?

04. After Summer (Giuseppe Arcimboldo, 1563)

Sour Summer, Hyunjin Kim, 2025

Summer, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, 1563

This photograph reimagines Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s Summer as a contemporary seated portrait. Instead of a face literally constructed from fruit and crops, the season appears through clothing and texture: a floral dress, sheer patterned socks, and a mass of plant-like fibres spilling from the chair like an overgrown field. The sitter leans forward in a slack posture, her body slightly folded in on itself, with an almost sulky expression that sits at odds with her carefully styled look. The title Sour Summer twists Arcimboldo’s original and hints at a season that appears lush on the surface yet carries a faintly acidic aftertaste.

Within the series The unseen in the seen, this image looks at how ideas of femininity and "the joyful season" are staged through fashion. Summer is often imagined as light, bright, and carefree, but the body here appears tired and weighed down despite the vivid costume. The work asks what happens when the roles we are expected to perform – as women, as subjects of fashion imagery, as the face of a season – no longer align with how we actually feel.

The photograph searches for its answers in details smaller than the face. The hunched posture, shoulders tipping forward, the loose weight of the hands and legs, the way the dress and fibres spread almost excessively around the body – all of these elements record the mismatch between styling and state. On one level, the scene presents a perfectly orchestrated summer image; at the same time, the body quietly releases fatigue and resistance into the frame. Following these small clues, the viewer is invited to sense how far the sitter’s lived summer might be from the one she appears to embody.

05. After Boy with a Basket of Fruit (Caravaggio, 1593)

Fruit Held Close, Hyunjin Kim, 2025

Boy with a Basket of Fruit, Caravaggio, 1593

This photograph reimagines Caravaggio’s Boy with a Basket of Fruit as a contemporary portrait. In the original painting, the boy turns his body towards the viewer while holding a basket lifted to chest height. His bare shoulders and the overflowing fruit are often read together as signs of sensuality and abundance. In this version, the basket disappears. Instead, a slender sitter in a white mesh tank top and red printed jeans pulls a small cluster of oranges tightly against their torso. The arms cross the body in an almost embracing fold, and the fruit is wedged between skin and fabric. The dark background and soft, diffused light recall the intimacy of Caravaggio’s painting, but the pose is far more closed, and the expression quieter and harder to read.

Within the series The unseen in the seen, this image moves the gesture from Caravaggio’s original — the act of extending fruit out towards the viewer — into the interior of the body. The fruit no longer appears as a gift being offered outward; it is gathered in and held close. The sitter seems unsure whether to show it, protect it, or simply endure its weight. The crossed arms function both as an embrace and a boundary. There is a willingness to be open to someone, and at the same time a refusal to hand over more than a certain point. The overflowing basket of the original image turns here into a question that feels specific to today’s image culture: how far am I willing to give myself away?

In this photograph, Caravaggio’s gesture remains, but its direction has changed. Rather than a boy extending a basket out of the frame, we meet a figure who pulls something inward and wraps themselves around it. A body marked by fashion and a degree of gender ambiguity seems to offer plenty to look at, yet still keeps something essential out of reach. The viewer is left to ask how much of what this person holds is actually visible — and what remains unseen.

06. After The Arnolfini Portrait (Jan van Eyck, 1434)

The Assumed Couple, Hyunjin Kim, 2025

The Arnolfini Portrait, Jan van Eyck, 1434

This photograph reworks Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait. In the original, a man and a woman stand side by side in a furnished room, surrounded by furniture, a dog, a chandelier and a convex mirror. Their joined hands and the carefully arranged objects invite us to read them as a significant pair, caught at a moment of marriage, contract or commemoration. In this version, that interior disappears. Against a dark backdrop, two young figures stand close together in elaborate outfits: on the right, a figure in a crown-like headpiece, veil and voluminous black skirt; on the left, a figure in a green checked robe, ruffled shirt and striped trousers. One gloved hand holds the other person’s hand, while the second hand hovers in mid-air, suspended somewhere between gesture and rest. With the room, furniture, dog and mirror removed, clothing, posture and the small distance between bodies become the only clues to their relationship.

Within the series The unseen in the seen, this photograph considers what we rely on to read a connection between two people once explanatory language and props fall away. At first glance they look like a pair on the threshold of a ceremony, yet the image never confirms exactly what they are to one another. That deliberate gap shifts attention away from any fixed label and onto the way pose, spacing and touch quietly signal how close – or how far – they might be.

Here, what matters more than facial expression are the arrangement and spacing of the bodies, the strength of the grip, the degree to which they lean towards each other. Viewers follow small details – the contrast between gloved and bare hand, the weight of layered clothing, the directions in which skirt and trousers fall – and from these fragments begin to imagine the temperature and tension between the two. The truly unseen element may not be their official status, but the private story each person constructs while looking.

This work gently reveals the line between what we believe we are seeing and what we are, in fact, inferring. It asks how much intimacy can be staged – and how much can remain concealed – through dress, posture and the smallest of gestures alone.

07. After The Arnolfini Portrait (Jan van Eyck, 1434)

The Assumed Partner, Hyunjin Kim, 2025

The Arnolfini Portrait, Jan van Eyck, 1434

This photograph is conceived as a companion to The Assumed Couple and, like that work, it draws on Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait. Instead of two figures standing in a furnished interior, only a single figure remains against a dark studio backdrop. The sitter wears a crown-like headpiece and veil, layered pearl and cross necklaces, a black lace top and a voluminous crinkled skirt cinched with an ornate belt. Their arms are held behind the back, tightening the torso, while the face turns in profile towards a light source outside the frame. Around the body, religious and ceremonial codes cluster – hints of queen, bride or saint – yet none of them fully fixes who this person is.

Within the series The unseen in the seen, this image shifts attention to the single body that might occupy one side of a double portrait. With the partner and the room removed, identity has to be read almost entirely from costume, posture and direction of gaze. Viewers trace the veil, jewellery, the pressure of the belt at the waist, the volume of the skirt, and are invited to think of roles – spouse, companion, central figure in a ritual – but the photograph never confirms any of them. The surface of a role is carefully put in place; the person who might fill it is left open.

The turned-away face and arms folded behind the back place the figure firmly at centre stage, while also keeping a certain distance intact. Everything seems clearly visible, yet who this person is and what they feel remains withheld. This work quietly asks how much of a life can be grasped from the outward signs of a role alone, and how far the rest must be completed in the viewer’s imagination.